ON Monday night at Martin Margiela’s

runway show, an event that marked the 20th anniversary of one of the

most influential and enigmatic designers on the global fashion stage

with a collection based on the highlights of his career, Mr. Margiela,

as is his custom, was nowhere to be seen.

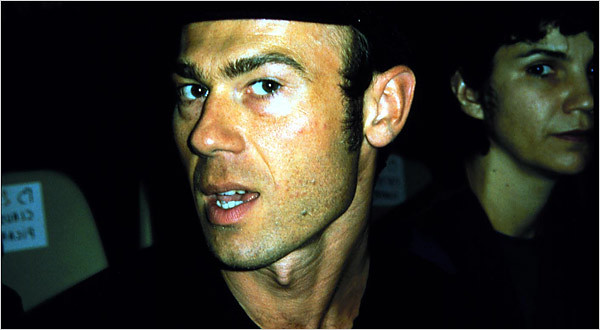

An anomaly in an industry that places enormous value on the image and

accessibility of its personalities, Mr. Margiela has maintained an

astonishing elusiveness. He refuses to grant face-to-face interviews and

has rarely been photographed, a provocative stance intended to

emphasize two dogmatic principles: first, that Mr. Margiela’s designs,

as confounding as they may be, should speak for themselves; and, second,

that the work he shows is inherently the product of a collaborative

team, not one person.

Hence, he does not take a bow at his shows, and all correspondence from

his atelier here is traditionally written in the plural form with the

signature “Maison Martin Margiela.”

This policy has led Mr. Margiela to be called fashion’s invisible man.

His influence, perhaps as great as that of any living designer, is less

often questioned than is his very existence.

Over the last year, however, the significance of Mr. Margiela as a

living, breathing person — albeit ultimately unknowable — has taken on a

new dimension. He has told colleagues that he wants to stop designing

and that he has begun a search for his successor at the house.

Early this year, Mr. Margiela, 51, approached Raf Simons, another well-regarded Belgian designer who at the time was renegotiating his contract with Jil Sander,

proposing that Mr. Simons take over the collection, according to

associates of the designers. But nothing came of the conversation, and

this fall Mr. Simons agreed to a three-year contract renewal with Jil

Sander.

On Monday, Renzo Rosso, the chief executive of Diesel Group, which

acquired Margiela’s business in 2002, added to the speculation that Mr.

Margiela had not been involved in recent collections when The

International Herald Tribune published this quotation from him: “We are

very happy with Martin, but for a long time he has a strong team and

does not work on the collection, just special projects.”

After the show on Monday, Mr. Rosso would not clarify Mr. Margiela’s

role, but said that the company was working with a headhunter to find a

designer “to complete our team.” Asked if Mr. Margiela was leaving, he

said: “Never say never, but I cannot imagine. I love him.”

Mr. Margiela’s importance was obvious at the anniversary show, which

included renditions of his great and witty conceptual designs: coats

made of synthetic wigs, bodysuits that fused parts of trench coats and

tuxedo jackets, and mirrored tights made to look like disco balls. But

his impact is even more obvious on the designers he has influenced,

including Marc Jacobs, Alexander McQueen and everyone else who showed pointed shoulders this season. Azzedine Alaïa recently called Mr. Margiela the last individual vision.

A graduate of Belgium’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts and a former assistant to Jean Paul Gaultier

in Paris, Mr. Margiela was among a group of designers from Antwerp who

caused a shift in fashion in the late ’80s by tearing apart and

reassembling garments at the seams, introducing techniques that would

have a lasting impact on everything from streetwear to haute couture.

The acceptability of shredded jeans, for example, owes a debt to Mr.

Margiela. But he has worked with such anonymity that only dedicated

fashion consumers instantly recognize his name.

“Martin’s influence in fashion has been quite vast,” said Kaat Debo, the

artistic director of the ModeMuseum, or MoMu, in Antwerp, where a

retrospective of Mr. Margiela’s work opened this month. “Often what you

see in the mainstream today is something that Martin introduced 20 years

ago, and in a shocking way. For example, the showing of unfinished

clothes with frayed hems or seams on the outside, which he did years

ago, are things today that are seen as quite normal.”

Mr. Margiela’s runway shows have been alternately electrifying or

humorous or sexy or just plain weird, as when he introduced a hooflike

shoe in 1992 that has since become a Margiela signature. More recently,

he presented a pair of $600 sunglasses that look like a censor bar. He

has shown coats reconstructed with a sock at the elbow or sleeves

protruding from the front and back; jackets with the sleeves turned

inside out into capes; and, in 1994, an entire collection based on what

Barbie’s wardrobe would look like if it were blown up to life size. (click)

No comments:

Post a Comment